Snow is falling over a long service road surrounded by prairie. A few small pump jacks eventually give way to an unassuming metal gate. It opens up to Strata Energy and its uranium mine. Inside a simple built office building, Ralph Knode, Strata's CEO, greets me. We walk over to a warehouse.

"We also will be entering what's called a restricted area," Knode says, walking into the area with hard-hatted workers setting up a field leach trial and the occasional quick alarm signaling a pressure test.

Banner for Strata Energy

Banner for Strata Energy

Credit Strata Energy

It's a large industrial room with pipes and ion-exchange vessels, into which uranium is hauled. Right now, those vessels pump an alkaline solution, the industry standard, through hundreds of nearby wells to recover uranium from aquifers below the surface. The solution used to pull the uranium out is essentially baking soda. But with weak uranium prices, that's not cutting it for Strata.

"We have said publicly that at today's prices, the performance of this mine is not sustainable in the current market environment," Knode says.

Uranium markets have been suffering from competitive renewable and natural gas prices for years, with plants closing down around the country. Wyoming is the number one provider of that uranium in the states.

Since last April, Strata has been pursuing a new approach to mining that would extract more uranium. It wants to use a low pH solution, or an acid solution. Knode says it would nearly double the rate of uranium recovery compared to the industry standard.

"We believe it'll be a game changer for us," he says.

The company lists several other advantages to the acid solution, like less water consumption, faster extraction and even improved groundwater restoration in some cases.

Strata has already passed the first few regulatory steps to make the switch. And soon, it could become the first mine to use an acid-solution to commercially recover uranium in the U.S.

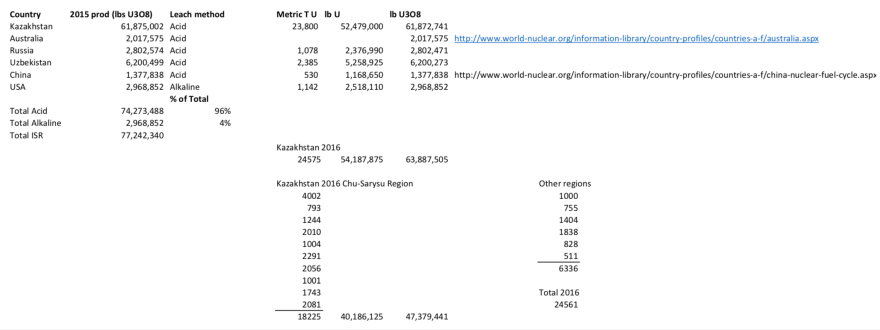

You might wonder why every company isn't using acid leaching if it's so effective. Outside of the U.S., they are. Acid leaching is the most common form of in situ uranium extraction in the world, according to data calculated from a 2017 World Nuclear Association report. Knode lists them off.

"Australia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia and China," he says.

But the discussion whether to standardize acid-leaching ended in the U.S. decades ago. Back then, several pilot tests raised concerns of groundwater contamination and restoring its original quality.

"Since that time, the Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission have really tried to get companies to shy away from acid leaching," Shannon Anderson says, staff attorney with the Powder River Basin Resource Council.

A 1992 International Atomic Energy Agency report seconds Anderson: "The difficulty for restoring groundwater following acid leaching led to exclusive adoption of alkaline leach systems."

It was difficult to restore because pH levels were too low and it took longer than the other solution. Plus, acid was causing a mineral to build up and hurt flow rate. Strata lists off several other concerns like a higher concentration of most dissolved constituents - much of that toxic elements. Strata's white paper also writes it needs to use corrosion resistant materials.

And it does just sound scary. Without all this context, it makes Wilma Tope nervous, who runs cattle near the mine. Her in-laws also live nearby.

"I don't want to be in the, more or less, discarded zone. So, I think all landowners, most do, feel that water's really precious," Tope says.

And she worries what would happen if the company had to close down given they're already in a tough spot. Tope knows that acid is good at pulling uranium from the rock - old tests show it's also good at pulling toxic elements out as well.

"And then my question is how is the clean-up going to go?" Tope says.

Strata's white paper lays out the disadvantages, but adds modern techniques have overcome early challenges. Knode says the company isn't asking for any standards to be changed for groundwater restoration. That means if toxic elements are brought into the water, they will be removed after the mine is shuttered. Only 1.5 percent of the solution is acid. The aquifers are confined, meaning there's no connection to drinking water. Knode even says restoration should take roughly the same amount of time, though old tests show it took longer.

With these assurances from the company, Powder River Basin Resource Council's Anderson says she doesn't oppose this project. She just worries about the precedent being set for all companies in the Powder River Basin.

"We're concerned generally about the state of the industry, and don't want to see risky processes and procedures just ok'd by our regulators knowing that groundwater could be risk," she says.

...

Back at the site, Knode points out to where all the change will happen. It's out in the snowy field, covered in black boxes sheltering wells underneath, where this site could become the first commercial site of acid-recovery in the U.S. for uranium.

"Everything you see out there will systematically be converted once we receive full approval from Wyoming DEQ," Knode says.

And if they're successful, both Knode and environmental advocates agree it could spark a tide change in uranium extraction across Wyoming and the country. Wyoming's Department of Environmental Quality is currently accepting public comment for the permit revision ?—that lasts until January 26.