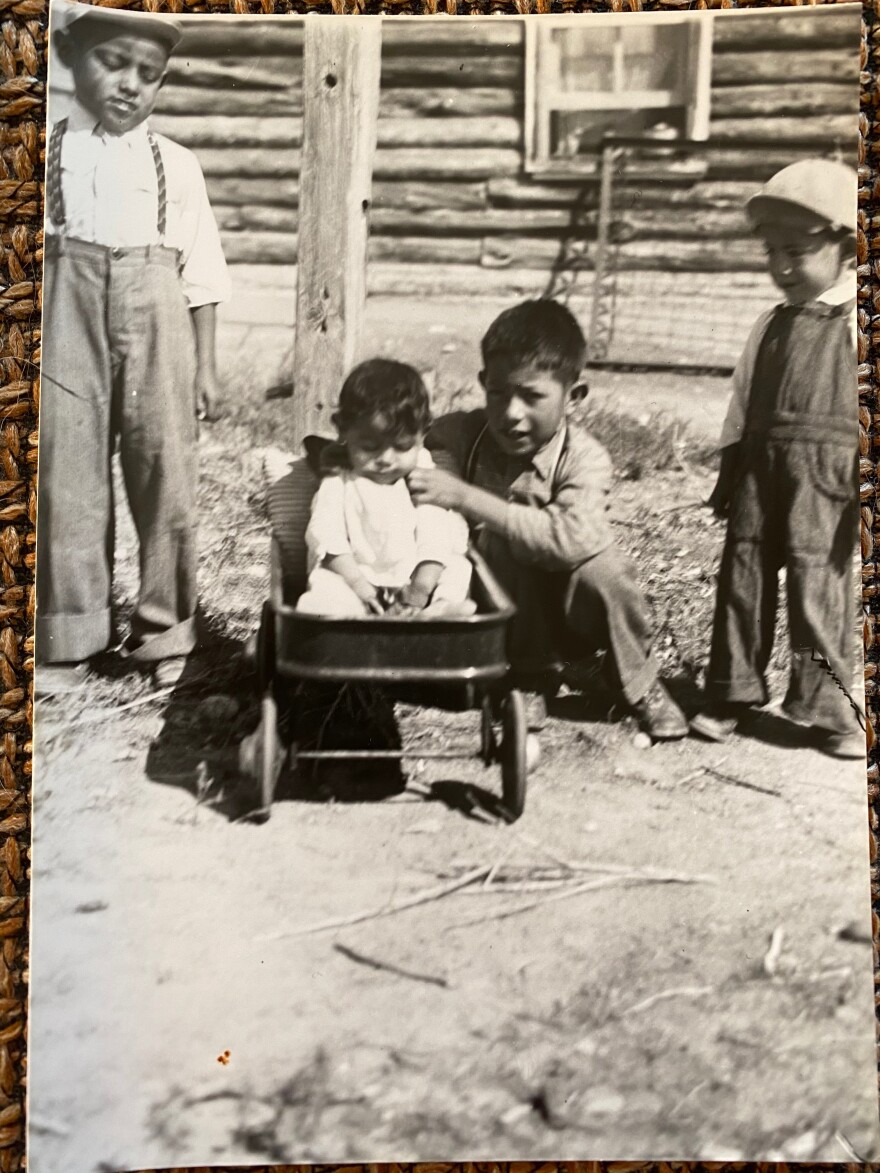

Felix Mercado was born in Worland in 1940. His parents, originally from Mexico, had traveled around the United States, eventually settling in Worland as sugar beet farmers where he and his older brothers grew up."I always look forward to going to school in the fall because summers, while we were working in the fields, etc., were a little hard," recalled Mercado.

Mercado said his childhood was normal. He played with friends and brothers. But when he entered first grade, he noticed something.

"We were kept separate. There were white kids living in our neighborhood. But none of them ever went to that school," he said.

For Mercado, this didn't seem too odd since the school represented his community that was mostly Hispanic on the west side of the railroad tracks, the same side the school was on. But there was one thing that happened daily that he couldn't ignore: he and his classmates were bused to the white elementary schools to eat lunch.

"We couldn't just go out and sit wherever wanted. They sat us in one area. And that's where we had to sit and eat our lunch," Mercado remembered. "The other kids, they could get up from wherever they were sitting and go for seconds or go get an extra piece of bread. We had to raise our hand and they would bring it to us."

Turns out, Mercado was attending what was known as the "Spanish School." A school that was built in 1936 specifically to segregate Mexican migrants from whites.

Gonzalo Guzman teaches at the University of Washington. He studies Mexican segregation education in the Mountain West. His interest is personal.

"My great grandfather was actually recruited from Mexico in 1919 to come to Worland, Wyoming."

Guzman grew up in a community in Washington state where many had come to after leaving Worland due to the way they were treated.

"They compare it to the experience of African Americans in the Jim Crow South," said Guzman. "That they treated us so badly in Worland, Wyoming, they even made us go to our own school."

As Guzman started researching what was known as the "Spanish School," he found records of Worland school officials saying they shouldn't segregate Mexican children.

"In the 1920s, there were actually a lot of school officials opposed because they're like, 'You can't Americanize children by segregation.' They were like, 'This is not the best way to do this.'"

Then the Great Depression happened. People lost jobs and opportunities decreased. Guzman said all of the sudden Mexicans posed a threat.

"The psyche of people in Wyoming, white people in Wyoming, [was] like, we need this to reaffirm a certain identity," he said.

Guzman said it wasn't just Worland. During the 1930s segregated schools and classrooms popped up all over the state. Torrington, Powell, Lovell and Deaver were among those that had similar setups. Guzman was able to find mention of Mexican classrooms or separate buildings for Mexicans on school records. He said Worland stands out because they applied for and received federal relief as part of the New Deal specifically to segregate Mexican and white kids.

"That's the first line that they say immediately. And it went to Cheyenne, so [it] got state approval, and local approval and county approval," he said. "So this was a concert of people working together to segregate these kiddos."

On a chilly February day, I drove down to visit Worland historian John Davis. Davis directed me to the building that was built to be the Spanish School. We crossed over the tracks, and there is a H-shaped red brick building.

"It's two stories, and I don't know exactly how the school arrangements worked," Davis described as we stood in front of the building. It was much smaller than I expected.

Davis, who grew up in Worland didn't know about the segregation until 1955.

"I remember that distinctly because I was in the sixth grade," Davis recalled. "And for the first time, there were Hispanic kids, including a very pretty Mexican girl who sat right in front of me, beautiful black hair, I remember."

"Brown vs. The Board of Education'' was decided by the Supreme Court the year before in 1954. That's the case that ordered school integration.

"I think that's probably what happened here," said Davis. "The school people said, 'We can no longer justify segregation of the kind that existed.'"

Davis said when he was growing up, racism towards Hispanics was obvious. There were signs in restaurants, bars and other establishments that said "No Hispanics allowed."

All Hispanics, like Mercado, lived on the west side of the railroad tracks. But Mercado went off to the university to become a pharmacist, came back and bought the local pharmacy. He did well.

"When I got married, my wife and I bought our home. There were people that weren't happy to see us move into that neighborhood," said Mercado. "Now, we're [Hispanics] all over the town."

Today, he said he rarely sees any acts of discrimination in Worland. And the town still has a pretty large population of Hispanics for the state. But Guzman said this history has mostly been lost.

"Another sad legacy of this school is how much has been lost. Because it's been so under studied, and this is why there's such a push now to get this recognized," he said.

The push is to get the "Spanish School" on the National Register of Historic Places so that its memory isn't lost.