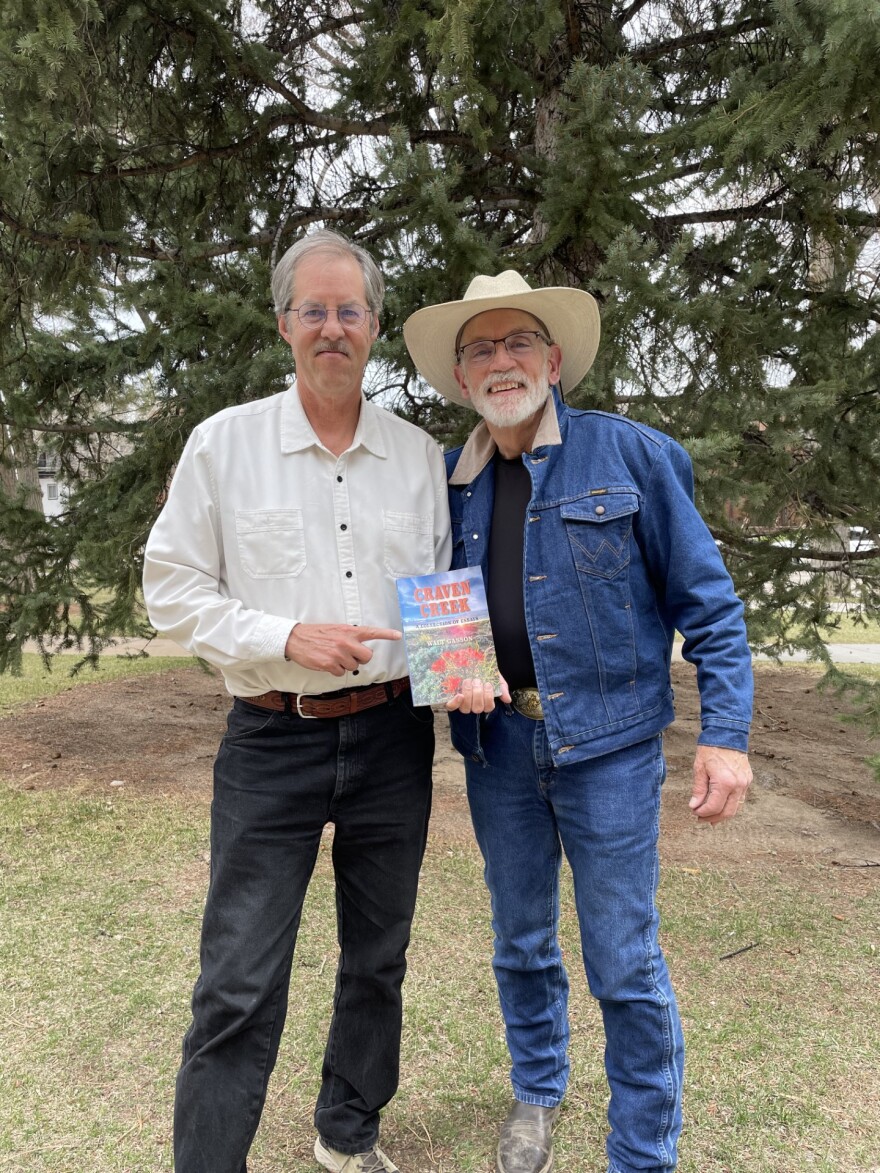

Wyomingite Walt Gasson has published award winning essays in “Wyoming Wildlife Magazine,” “High Country News” and “Trout Magazine.” They’re now included in a new book titled “Craven Creek.” Wyoming Public Media’s Grady Kirkpatrick recently spoke with the author about the essays.

Editor's Note: This story has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Grady Kirkpatrick: Walt Gasson, you’re a fourth generation Wyoming native, and these essays were inspired by your family and place and storytelling around southwestern Wyoming. There's some interesting Wyoming history in this collection. Let's start with Craven Creek near the little town of Opal, Wyoming.

Walt Gasson: Craven Creek is really not much of [an area] honestly, Grady. It's a small stream north of Opal, Wyoming. Opal, Wyoming is a very, very small community. And the thing about Craven Creek that ties it to our family is that our family's ancestral, if you will, sheep ranch straddled Craven Creek. I think it's a small place in a big land, just like much of the interior West. And I think there are thousands of families just like ours, that are tied to places like that. And I think that makes those families special.

GK: Tell us about your grandfather, the man you're named after, Walt Gasson. Old Walt, isn’t that right?

WG: Old Walt. Yeah, I never met the man, never saw his face, never heard his voice. He died many years before I was born. But he was a man of the sagebrush sea. He was a stockman, by his own description. And for much of his life, he worked for other people, big sheep outfits in southwestern Wyoming. His job as a foreman was to ride from one band of sheep to the next, and make sure the herder was still there and make sure they had the supplies they needed. Help them in any way he could. A remarkable thing about old Walt: He was a small man, not very big, like many of the really good cowboys I know. And he was at heart a buckaroo, he really was. He always rode an ugly horse. I have no pictures of my grandfather riding a beautiful horse. They're always ugly. And, my grandson pointed out to me one day, when we were talking about that. He said, “Well, grandpa, maybe it's more important that he had a horse that could go 30 miles without needing a drink of water, than to have a pretty horse.”

GK: Good point. There's also historical references for the early 1900s, around the town of Green River where your parents were from. Tell us about those early days and tell us about your mom and dad and Green River.

WG: My mom and dad grew up in a one stoplight town. I grew up in a one stoplight town, before Green River began to grow rapidly in the ‘70s and ‘80s. But it was a railroad town. It was a blue collar town above all else, and it was a place that was ideal for a young man like me or young person, really, of that time, because I tell people, Grady, that I could have taken off walking or ridden my horse from my mom's backdoor in Green River to either Idaho, Utah or Colorado, on public land unimpeded.

I had as much freedom growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s in Green River, Wyoming as a young Shoshone boy might have had a century and a half before. And I think that experience, that degree of freedom and that kind of connection to the land – multigenerational, I guess, connection to the land – is something that has value like the place where we live.

GK: I guess your mom wore a lot of different hats, but she was also a librarian. And there's actually a room in the Rock Springs library named after her.

WG: The Grace Gasson Room in the White Mountain Library, where I'll be doing a reading here on the 15th of May. Very much looking forward to that. My mom was an interesting story. She grew up in – what we would consider now – in abject poverty. She never met her father. Her father died during the Great Influenza epidemic of 1918. She was born in January of 1919. And he had died months before. Her mom was devastated. She had difficulty bonding with this little baby. But as this little girl grew up, she grew up with a love of books and learning. And during the Great Depression in her teenage years, landed a job through one of the great New Deal programs at the library. She came to love that work. When high school came, she had a full-ride academic scholarship offer from UW. [She] passed it up because her $50 per month salary was all it was keeping her and her mom above water. Went on, rose to be the chief librarian of all the libraries in Sweetwater County, and then got married and dropped out of the workforce. Later came back in and rose again to be chief librarian in Sweetwater County, and built new libraries and built relationships that endure to this day.

GK: That's great. I'm talking with Walt Gasson about his collection of essays titled “Craven Creek” from Wordsworth publishing, available in Wyoming bookstores and online.

Many of the essays explore the big wonderful Wyoming backcountry, the mountain ranges, the wide open spaces and the rivers with stories from hunting and fishing trips. You mentioned in the essay about the Red Desert and “The Haystacks Elegy” that perhaps 21st century America can't be expected to recognize things of intrinsic worth. Can you elaborate just a little on that thought?

WG: I stole the term, quite honestly. Wally McRae, old eastern Montana rancher and friend, did a poem called, “Things of Intrinsic Worth.” And I think what he was trying to say is that sometimes we lose track of things that have real value. And in that particular essay, we're talking about wilderness with a small w. A place that took all day to get to in 1965. And my dad Gus and I will go to The Haystacks every so often. He loved the place because it was so far from any place. You had to work to get there. It was actually a place that Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch used as a campsite, because they could get high in elevation and watch their back trail to see if anybody was following him. But it was a trip for me from the 20th century into the 19th century, when everything was done by horse, when wild country was wild, in 100 miles in any direction.

GK: And the final essay in the collection, “The Homeplace.” Tell us about the history of that.

WG: Grady I need to tell you a little bit about my parents. My father was a conscious quintessential son of the sagebrush sea. He was as comfortable halfway between Jeffrey City and Warmsutter as he was in his own living room. My mom, on the other hand, did not come from a family where the outdoors was a thing. And so upon their marriage, he concluded pretty quickly that he was going to have to figure out a way, if they were to enjoy a wild country together, he was going to have to figure out how to put a roof over her head. Because she wasn't into sleeping on the ground. She wasn't into cooking over a fire. She needed at least a modicum of civilization to be happy there. And so they hit upon the idea of building a cabin on the west side of the Wind Rivers in the Bridger Teton National Forest. And they went in partnership with my aunt and uncle, my dad's sister and her husband, and built this 20 by 31 room cabin from logs that were logged nearby. The fireplace came from rocks from South Pass or Big Sandy. And that became and remains the spiritual center of the Gasson family universe. I tell people that, you know, it's kind of like the family ax. We still got the same ax that we had in 1958 when they built the cabin. We've only replaced the handle twice and the head three times. The pieces and parts have been replaced. The genuine article, if you will, remains the same. And if you ask any of my children, “What are your best memories of growing up?” They will tell you a story about the cabin in the Big Sandy country.