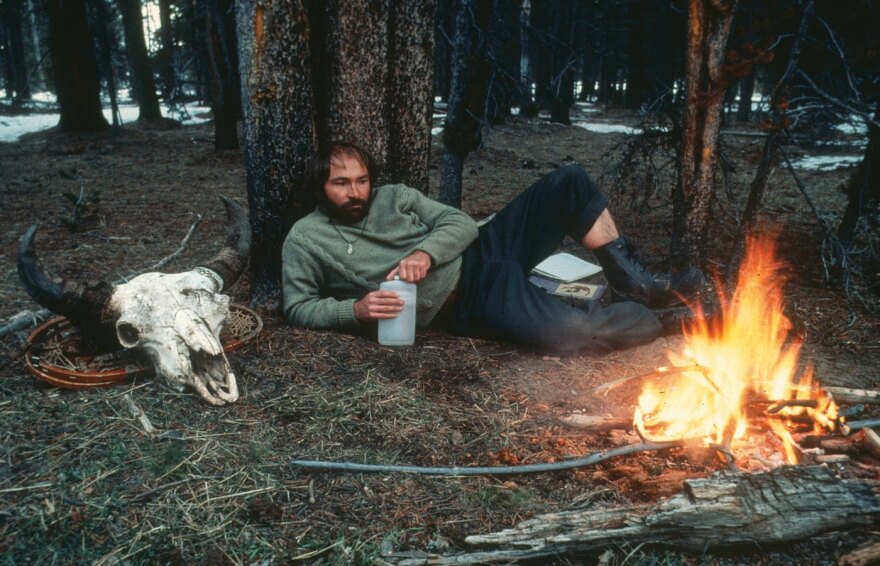

Doug Peacock is an American author and wildlife activist who’s spent the majority of his life studying bears, primarily in the Montana and Wyoming areas. He recently published a book called "Was It Worth it? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home."

It is a collection of Peacock's essays, following his outdoor adventures across the globe starting in the 1960s. Sometimes he's solo, other times he is with his closest friends, like Yvon Chouinaird, the owner of Patagonia, and Doug Tompkins, the founder of The North Face.

Peacock spoke with Wyoming Public Radio's Caitlin Tan about the book.

Caitlin Tan: You know, your stories range from all over the globe. At one point you're in Yellowstone, living off the land after coming back from Vietnam. In another chapter, you're escaping the feds in a drift bow in Montana. And then later you're in Mexico in the Sierra Madre trying to find the last Mexican grizzly bear. To give people a taste, could you read the opening paragraph to the chapter titled, "Treasure in the Sierra Madre in 1985"?

Doug Peacock: Sure, this is a tale of going down to the Sierra Madres just south of the colonial town of Casas Grandes:

I unscrew the bottle and pass the tequila to the driver of the pickup who already holds a can of Tecate between his knees. He looks like he could use a few drinks. The international border crossing in Agua Prieta resembled the Three Stooges shakedown. The board border police held us up for two hours until we bribed them with half our pocket cash. Later at the archeological ruin at Old Casas Grandes, we almost went to jail. Tourists and people like us need to tread carefully in this part of the Northern Mexican frontier.

Anyway, we stumbled down the highway, you know and rather carelessly, but we ended up in a very wild and beautiful place in Mexico that held the last great wildlife of the Sierra Madres. And also, my first jaguar backtracks us for 14 miles and sniffed around our fire one night scaring the grass out of me.

CT: Doug, I wanted to ask you about grizzly bear hunting. In the chapter "Why I Don't Trophy Hunt," you mentioned that the core argument for hunting Yellowstone's grizzlies is for public safety and that it will "make people safer by instilling in grizzlies a fear of humans." Now you don't agree with this, and I'm curious if you can kind of walk us through your thoughts on that.

DP: There's no truth in that whatsoever. You know, we're able to form relationships with grizzlies. As long as you're not a threat to a mother of grizzly cubs, you're in no danger from grizzlies, ever.

When my daughter and I were on the top of a small butte in Yellowstone Park, it was blowing like hell up on the top. I caught her eyes looking over the hill and coming over the rise right next to us was a mother grizzly with a yearling cub. And you know, the only thing I remember saying to Laura was, "Don't move." And this mother grizzly reared and went through her whole spectrum of checking out whether we were going to be a threat to her cub or not.

All of those things that people think are aggressive signs are not. It's the bear trying to determine if you're a real threat or not.

We didn't move a muscle, and that bear settled down and came walking over the hill right towards us with her cub behind her like 20 feet away. That bear proceeded to nurse her cub for about seven minutes, right in front of us.

The reason we don't have experiences like that is we never give them the chance to flesh out the actually incredible social behaviors they exhibit among themselves and between each other. And also they do the same thing to a limited extent with human beings.

CT: Doug, I'm gonna have you read a little bit from the chapter "Monsoon." You're in Baja, and you mentioned you’re fleeing a malady of sorts, some PTSD from Vietnam.

DP: So, I'm blasting down Baja alone in the middle of summer, just to get the hell out of my domestic life. I wasn't doing very well back then.

The problem seemed to be that I wanted a life beyond the war zone, but not in the world I had come back to. I wanted to live inland. I remember leaving before Southeast Asia, the grand topography of the American West and Rocky Mountains. Returning, I found it transformed by drilling rigs, power plants belching black death, connected spider-like by hundreds of miles of power lines, with clear cuts and development sprawling across the mountains, deserts and plains. After Vietnam, I couldn't bear the destruction of that particular beauty.

CT: In that passage, you reference the drilling rigs and the changes in the landscape when you've come back to the Montana/Wyoming area. In more recent years, how do you feel about everything, and do you feel like things have changed, even over the past couple decades?

DP: Yeah, unmistakably and not unexpectedly. The question that subsumes all others is climate change. It's just so gigantic. There's not one species of animal or one eco-type on Earth that's not affected by it, you know, and that is the beast of our time.

CT: In the last chapters, you focus a little more heavily on human-caused climate change. You even mention how COVID-19 is kind of this indirect result of human greed. In the passage from the chapter, "The Perfect Bait For An Outbreak," you explore what our role as humans is here on Earth. To me, it's really fitting with where everything is right now in the world. Can you read that for us?

DP: When it is indeed our time to walk off stage with the mammoths, what might be the measure of our character at the end of our tour? After peering into the abyss, how do we behave? There is great joy in doing the toil of the world, fighting for wild causes, saving pieces of the magnificent, natural world.

There's plenty of work. Do your job with decency and an open heart. Love your brothers and sisters in all actions, in all relationships. Speak the truth. Extend your innate empathy to distant tribes and strange animals. Arm yourself with friendship and love the Earth. Remember your elders. Walt Whitman said, "Resist much, obey little." Or as Ed Abbey noted, "A patriot must always be ready to defend his country against his government." Hold nothing back. Join the tribes in their dignified defense of Native rights. An Indigenous viewpoint should replace all notions of Western wildlife management. Respect this militant resistance and embrace the necessity of civil disobedience. What’s right isn't always legal and vice versa. Consider getting arrested.

CT: It leaves a lot to ponder.

DP: Yeah, indeed. Those are the giants of our lives – all our lives.