Growing up, Lavina Antelope and her little brother Andy were close. She calls him the baby of the family, even though he wasn't the youngest of his nine siblings. She says he was funny and tenderhearted. In his final years, he struggled with severe and chronic alcoholism. Lavina Antelope worried that her brother's addiction would kill him. She never imagined she would lose him to police violence.

"I've had a lot of deaths in my family," she said. "But you know what? This is the first time a family member has ever died of a gunshot."

On September 21, 2019, a Riverton Police officer was trying to arrest Andy Antelope, a 58-year-old citizen of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, for public intoxication. According to a report from the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation, or DCI, Antelope wouldn't comply. The officer put Antelope, who was sitting at a picnic table outside of a Walmart, in a wrist hold and tried unsuccessfully to bring him to his feet. While the officer was distracted by a bystander, Antelope pulled a six-inch knife and swung it into the officer's chest, striking his armored vest. The report states that the officer ordered Antelope to drop the knife, and that when Antelope appeared ready to strike again, the officer shot him in the head at close range.

"That really took a big ol' blow. It really hurt me a lot, you know? And it still hurts to this day," Lavina Antelope said.

In December of 2019, Riverton Police Chief Eric Murphy expressed sympathy for Antelope and his family members, but called his death unavoidable.

"It's very unfortunate what happened. But what everybody needs to realize is Anderson Antelope made this decision. Not the officer. When [Antelope] pulled out that knife and shoved it in our officer's chest, he made that decision," Murphy said.

But Antelope only tried to shove a knife into the officer's chest. Thanks to his armored vest, the officer was unharmed. Still, Murphy says the officer was acting in defense of himself and others on the scene.

Antelope's family members and others who knew him well have doubts about whether he could have posed a real physical threat. He was 58-years old and in bad health, largely because of his addiction. He had poor balance and struggled to get around without help.

After reviewing the DCI report, Fremont County Attorney Patrick Lebrun announced that the officer's use of lethal force was appropriate under Wyoming state law. Lebrun declined to charge the officer, and his name has not been officially released to the public.

Lavina Antelope was counting on the opportunity for the public to review the evidence at an inquest planned by the Fremont County Coroner's Office. But that inquest was suspended when it became clear that city and county officials would not support it.

"To me everything is just like a big cover-up for the officer that killed my brother. They're sweeping everything underneath the rug. They don't want the truth to come out," she said. "That's what I'm thinking, and that's what a lot of people are thinking."

Coroner's inquest disputed, suspended

Under Wyoming state law, county coroner's have the power to convene an inquest jury, made up of three citizens chosen by the coroner, to consider the "means and by what manner" an individual died. Coroner's inquests are not criminal trials and don't have the power to recommend prosecution. Instead, Fremont County Coroner Mark Stratmoen said, they're a public transparency tool. It's his office's policy to convene an inquest any time someone is killed by law enforcement in Fremont County.

"Because, and it's obvious in the contemporary and recent history of the country, that transparency is an important aspect of those incidents," Stratmoen said.

But Fremont County Attorney Patrick Lebrun opposed an inquest into Antelope's death, in part because the criminal justice system had already reached a determination in the case.

"The purpose of a coroner's inquest is to determine cause and manner of death. In this case, the cause and manner of death was never in dispute," he said.

Lebrun said that allowing the inquest jury to consider other matters, including whether the shooting was justified or avoidable, would be improper and unfair. He also believes it would be incongruous with state law. Additionally, Lebrun pointed out that Stratmoen's inquest wouldn't have followed some of the rules meant to ensure fairness in a criminal trial, including impartial jury selection and the opportunity for cross-examination.

"[Stratmoen] carries on and he says, 'Well it's not adversarial, so my process is different.' Well the thing is, it is the adversarial process that gets to the truth," Lebrun said.

Stratmoen says it's by design that a coroner's inquest operates differently than a criminal trial. Still, without support from the County Attorney's office, which is responsible for enforcing subpoenas in a coroner's inquest, Stratmoen said he had no choice but to suspend it. If the inquest had been allowed to go on, Stratmoen believes it might have provided the community with some closure.

"That sort of transparency and understanding can a lot of times prevent further public questions and disruptions down the line," he said.

"Public inquest now!"

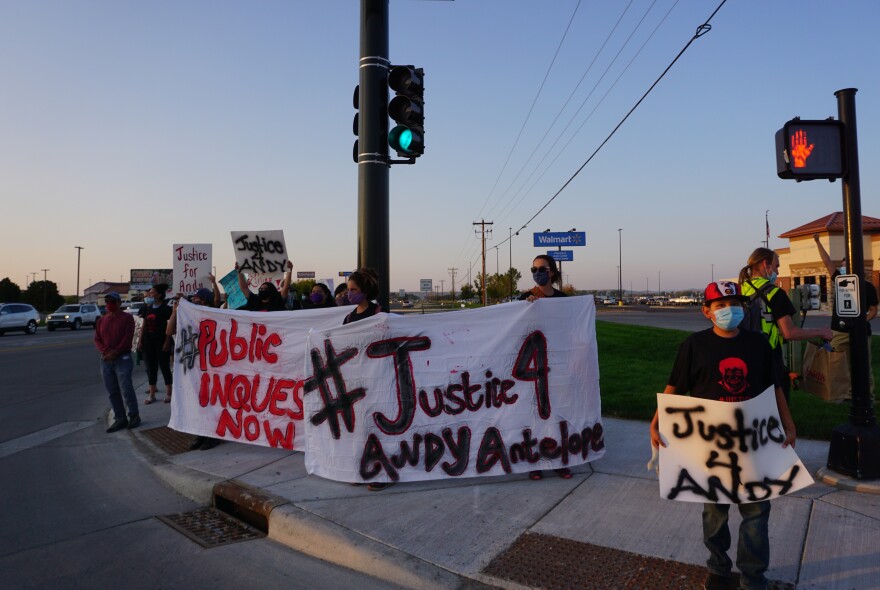

A year to the day after Antelope's death, about 50 community members marched through downtown Riverton demanding that the coroner's inquest go on. They chanted "Justice for Andy!" and "Public inquest now!"

The hope for these demonstrators is that an inquest would provide a forum independent from the criminal justice system for the public to consider the circumstances surrounding Antelope's death. Not just whether the shooting was legal, but how and why a public nuisance call ended with a man being shot in the head.

Riverton resident Larry Wallace attended the demonstration. He knew Andy Antelope personally, knew his physical limitations, and he believes it's possible the shooting was justified. He just finds it strange that local officials would stand against a public airing of the facts.

"When an inquest is denied and certain questions are still unanswered, I think it creates this atmosphere of doubt," Wallace said. "We need questions to be answered, we need honesty, and we need a plan to move forward which will help to prevent tragedies like this from happening again."

The issue also came up at a September meeting of the state legislature's Select Committee on Tribal Relations. During scheduled testimony on a law enforcement bill that was unrelated to the Antelope case, Patrick Lebrun called into question the transparency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Police Department that operates on the Wind River Reservation. Fort Washakie Representative Andi Clifford fired back.

"Here's the complex jurisdictional issue I want to make a point on: It's Patrick LeBrun, and it's our tribal member who got shot at Walmart, Anderson 'Andy' Antelope. That's my issue," Clifford said.

"If we want to talk about local control and transparency, we never got justice. The people never got justice."

Clifford's comments led to calls for decorum from other committee members. However, Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribal leaders present on the video call thanked Clifford for bringing up the issue and pushed Lebrun to respond.

"Representative Clifford apparently forgot that I provided the entire case file on Anderson Antelope to the media," LeBrun wrote in a statement the following day.

Under Wyoming public records statute, law enforcement agencies are typically required to release closed case files to the public upon request.

After Antelope's death, the Riverton Police Department purchased body cameras. Chief Eric Murphy hopes the cameras will protect his officers from accusations of misconduct. He has also said that his department and the county attorney's office have been fully transparent, and that further probing of the case isn't necessary.

Whether a coroner's inquest would have satisfied the Antelope family's questions about their relative's death is unclear. But they say it would have been an earnest attempt. Lavina Antelope believes the inquest should go on not just for her brother's sake, but to set a precedent.

"We don't want anybody to go through the hurt that we went through," she said. "And I'll tell you what, it's a hurt that's going to sink in and I don't think it will ever go away."