Part1

Mitch Homma was cleaning up his grandmother’s house in California after she passed away in 2004. Tucked away in a closet was something he had never seen before.

“We found, I don't know, like 18 boxes full of documents and photos of the family history going back from Japan,” he recalled recently. “And then, of course, all the World War II documents and photos since.”

Homma’s grandparents and parents didn’t talk about their World War II years much, but these boxes contained the answers.

“We didn't really learn stuff until after 2000,” he said. “So that's what started the long journey of putting all the pieces of the family history together.”

Homma wanted to know what happened to his family at Amache – one of the 10 main Japanese American internment camps set up by the U.S. government during the war.

It all started in early 1942, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Anyone deemed a threat to national security by the military could be relocated inland. Due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese Americans were seen in a different light by the government.

Some community leaders were arrested by the government. Radios were confiscated inside homes close to the West Coast. Families had to sell their stores for pennies on the dollar. Homma said his family did what they could to hide any signs of their Japanese heritage.

“He [my dad] remembers grandfather draining the koi pond and having a big bonfire, burning a lot of Japanese items,” Homma said.

It is estimated that mo re than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to relocate to internment camps. They could bring one suitcase of belongings, but the rest was taken from them.

“Dad remembers sitting on the curb and family heirlooms being thrown in the back of the car, back of the trunk for the FBI vehicle,” Homma said.

His dad and more than 7,000 other Japanese Americans were first taken to the Santa Anita Assembly Center outside of Los Angeles – a horse racing track.

“No matter how much his mom, my grandmother, you know, bleached and tried to clean the horse stalls, it still smelled,” Homma said. “They definitely knew they were living in a horse stall.”

They lived there for six months before they were transported by train to Amache in 1942. At its peak, the camp had more than 7,000 evacuees living in one square mile of land.

The guards were really strict when they showed up, according to Homma. They were put into small, poorly insulated rooms that only had a stove, a lightbulb and some cots.

“They pretty much had to make themselves, you know, pillows or cushions,” he said. “They were given army blankets and stuff like that.”

Everything they did was shared, from the bathrooms to the mess hall. Homma says it was a complete change of culture.

“That was one breakdown of, you know, your core traditional family values,” he said. “All of a sudden, you know, your family dinners are now your family dinner with 100 of your closest friends.”

Those who were held at the camp were fed meals that differed greatly from what they were used to. With the exception of white rice, they were served eggs, potatoes, and hot dogs, to name a few. It was a big shock to Homma’s father, so he stopped eating.

“I was told he lost, like, I don't know, like 50, 55 pounds before he passed away,” he said. “He [my dad] would mention growing up, ‘Amache took my father away.’ He was an 8-year-old little boy when his father died.”

Sanitation at Amache wasn’t the best, either. Derek Okubo’s relatives were also at the camp and felt the effects of it.

“I remember my grandma, she had mentioned to my cousin just how many times she had to filter the water in order to get it clear so that she could use the baby formula,” he said.

In moments like those, the parents did their best to be positive around the kids.

Okubo recalled, “I had asked my dad, ‘What was it like there at the camp?’ And he said, ‘There is a fine line between hope and despair on a daily basis.’ When you think about parents with young children, you know, the parents are trying to be hopeful, even though on the inside they're dying.”

It also strained the relationship between Japanese Americans and the American government – even though many served in the U.S. military, they were still fighting against Japan. Homma’s father served in the Marine Corps many years after his imprisonment, but Homma was curious if his dad would have served if he was old enough at Amache. He asked him at the nursing home shortly before he passed away.

“I thought for sure he would answer in two seconds and say, ‘Yes, absolutely,’” he said. “And he actually thought about it for 15 seconds and said, ‘I don't know.’ [I replied,] ‘What do you mean you don't know?’ And he again, he repeated, ‘Amache took my father away. I don't know if I could've served the country with my family behind barbed wire.’”

Okubo’s relatives had the same distaste.

“I asked grandma, you know, ‘What can you tell me about the camps?’” he asked. “And I saw a look come over her face that I had never, ever seen before. And it was one of anger, of pain, of disgust. You know, I had never seen that look. And she just shook her head and got up and left the table.”

Despite these conditions, the survivors made Amache home. They held art classes to bring life to their barrack walls. They made snowmen in the winter and planted gardens in the summer.

Over time, the guards loosened up a bit. The kids were allowed to go into town as long as they were back before dark. They could climb the water tower to take photos.

“The cowboys would ride up to the barbed wire fence and they'd give the kids short rides,” Homma said, recalling memories his father told him. “They'd walk to town and get a soda or something from Newman's drugstore.”

But it wasn’t easy. They were still living behind barbed wire with armed guards.

“I remember hearing comments that, ‘Oh, the Japanese were put into the camps to protect them from harm from the outside,’” Okubo said. “Which was B.S. If that was the case, why were the guns pointed in and not out?"

When the war ended in 1945, the Japanese Americans were let out of Amache with $25 and a bus ticket to restart their lives. Okubo’s grandparents worked hard despite the pain they had endured and opened a store in Denver. It was called Ben’s Super Market, on 28th and York near the zoo.

“I remember asking my dad, you know, how did they get that determination?” Okubo said. “And he said, ‘Well, sometimes the best form of revenge is to succeed.’”

This determination is not unique to Okubo’s family – it was a principle shared by many.

“Gaman means persevere … that principle, first of all, that allows people to accept it,” said Carlene Tinker, an Amache survivor.

Tinker said they pushed through by clinging to their cultural values.

“This other principle also, I believe, of Buddhist origin and that’s Shikata Ga Nai,” Tinker said. “And that is, it is what it is. You just accept it. It happened.”

Regardless of principles, Okubo knows what the United States did was wrong. He wants to make sure that this never happens again.

“After 9/11, you know, we heard the talk of internment camps again. And it was just like, haven't we learned?” Okubo said. “This country is supposed to represent all these wonderful values. And then when something like this happens, when the hate and the hysteria and the prejudice, we tend to forget it.”

Homma agrees. Stories like his are what he hopes Americans will never forget.

“All governments make mistakes, all ruling kingdoms make mistakes,” Homma said. “And it's what you do afterwards, right? Do you bury it? And so that mistake happens over and over and over again, you know, or do you learn from it?”

Part 2

John Hopper grew up in Las Animas, Colorado. It’s a small town where everybody seems to know everybody. But Hopper’s mom made a connection that stuck with him long after his childhood.

“My mother worked with a former survivor, Emery Nomura, briefly, but she worked with them,” Hopper said. “His wife … worked in the silkscreen shop.”

During World War II, the Nomuras were held at Amache, a Japanese American internment camp near Granada, about 60 miles away from where Hopper’s family lived.

Hopper developed a fascination with social studies and got his first job teaching at Granada High School. That’s when he got an idea.

“We’re right next door,” Hopper said. “We're a quarter-mile away from Amache. And I thought, ‘Man, this is an ideal situation to do a living history project.’”

He started gathering interviews along with his students in the early 1990s. They talked with Nomura and he provided addresses of people they should contact for interviews. They didn’t hear anything for weeks.

“So I said, ‘Maybe we did it wrong,’” Hopper said. “And then somebody called us from Denver – a long distance – and I took it at the school and she said, ‘Well, I have the questionnaire in front of me.’ I said, ‘Oh, you got one of them.’ She goes, ‘No, we've been passing it around.’”

Survivors and descendants started sending family heirlooms and artifacts from the camp. Eventually Hopper and the students ran out of space on the high school campus, so they moved everything to a local building in town.

“Did I think it was going to be like this? No, not not in my wildest dreams,” Hopper said. “We've got so many artifacts, we have to shift stuff in and out, making new exhibits all the time.”

Today, the museum has close to 1,400 artifacts that shed light on a piece of local history – everything from a stringed zither called a Koto, to saké bottles, to a print from the silkscreen shop where Nomura’s wife worked.

“Every object in here has a backstory,” Hopper said.

And he remembers the details of every single one – including a playing card from an illustrator known for his images of pinups.

“There is a Alberto Vargas card in there,” Hopper said this fall as he showed off a photo album to a group of tourists. “It was given to a gentleman that was in the 7E block. I believe it was. All the women signed it for good luck.”

Hopper doesn’t get paid for this, however. For the last 30 years, he’s volunteered along with his students to bring the Amache museum to life – from giving tours to cleaning it.

“They run this,” Hopper said. “They open it up, they vacuum, they mop the bathrooms, clean out the trash, keep everything up and running.”

Hopper allows survivors to come back and tell their stories at the museum, too. Mitch Homma’s dad and several other relatives were imprisoned at Amache, and Homma has contributed a lot to the museum.

“On the cot over there, that's my father's blanket,” Homma said to the tourists. “There's a light colored blanket, too. The light colored blanket is from the Amache hospital. And so that was probably grandfather's blanket when he passed away.”

The work of Hopper and his students has sustained Amache for years, and it does not go unnoticed by Homma.

“Those are the local guys, boots on the ground that are caring for the sites,” Homma said. “I'm actually super-fortunate to have a great group of grassroot stakeholders caring for different parts of the site, different projects, large and small.”

A hidden history

Amache is taught in Hopper’s history lectures. But he said that isn’t always the case with other teachers.

“It was a travesty in history and a very offshoot kind of history because it's not covered,” Hopper said.

Russell Endo understands this sentiment. During World War II, his family was incarcerated at a camp in Arkansas. When he was hired by the University of Colorado-Boulder to teach Asian American studies back in 1973, he knew a trip to Amache would be in his syllabus.

“I think it's important to actually be at the place where people have experiences that they're trying to learn about,” Endo said.

When he first started teaching about Amache, he said most of his students were of Japanese descent, so they were very enthusiastic.

“I think they were anxious to learn about where their families had been during the war or where their friends' families had been or other people that they knew,” he said.

Over time, as other students joined his class, there were different responses.

“Most of them had never heard about Amache and didn't actually know very much about Japanese Americans,” Endo said. “So I think the impact on them was much greater in terms of surprise and maybe dismay.”

Endo has since retired from the university, but he liked to give his students some questions to wrestle with, such as, “Who is considered an American?” He would also illustrate lessons with demonstrations, such as bringing in a copy of the Constitution and ripping it up. He said these concepts are important to understanding Amache.

“The stuff is just on paper, your rights don't exist unless people are enforcing them,” he said. “So what happened during World War II was a failure to enforce constitutional rights. And then we get into a discussion about how do people do this? And, you know, whether we're not doing this today.”

Endo has been working with some Denver-area public schools to add information about Amache to their curriculums, and he is set on seeing more schools do it. More importantly, he wants people to continue learning about Amache outside the classroom.

Digging up the stories

Hopper and Endo aren’t the only ones working to educate people about Amache. Bonnie Clark, an archaeology professor at the University of Denver, has been working at the site since 2008 to find artifacts that may have been left behind.

“We sort of walk back and forth across the surface of the site looking for remains of the things that people did to improve their life in camp,” Clark said. “The finds of that original work pointed out to me, you know, the ways that people were really kind of turning this place from a prison into a town.”

One big find was remnants of an ofuro. It’s a traditional Japanese bathtub that farm families would use to wash up. Those held at Amache built their own with cinder blocks because the camp only provided showers.

“It's one of the many ways that we've seen where people were, again, trying to sort of reclaim those things that make you feel human,” Clark said.

She excavates the site with her students, but also allows survivors to join her. Clark said these places and objects are like a time machine that helps survivors connect their stories to the bigger picture of history.

“I can take someone by the hand and walk them through the doorway of their families’ barrack or where their mother taught school, you know, and that sort of passageway to the past is very, very powerful,” Clark said.

Carlene Tinker is one of the survivors who has joined the search. She was at Amache when she was 3 years old. Decades later, she was there when the ofuro was found.

“I remember actually going to and fro with my mom and my two maternal aunts, and ours was way out in the open,” Tinker said. “That water can be used by other people who are also taking a bath. So not only was it a physical activity of cleaning our bodies, but it also, I think of this as a bonding experience between or among all four of us, my mom, my two aunts and myself.”

The ofuro was only one of the discoveries she made during the excavation in 2014.

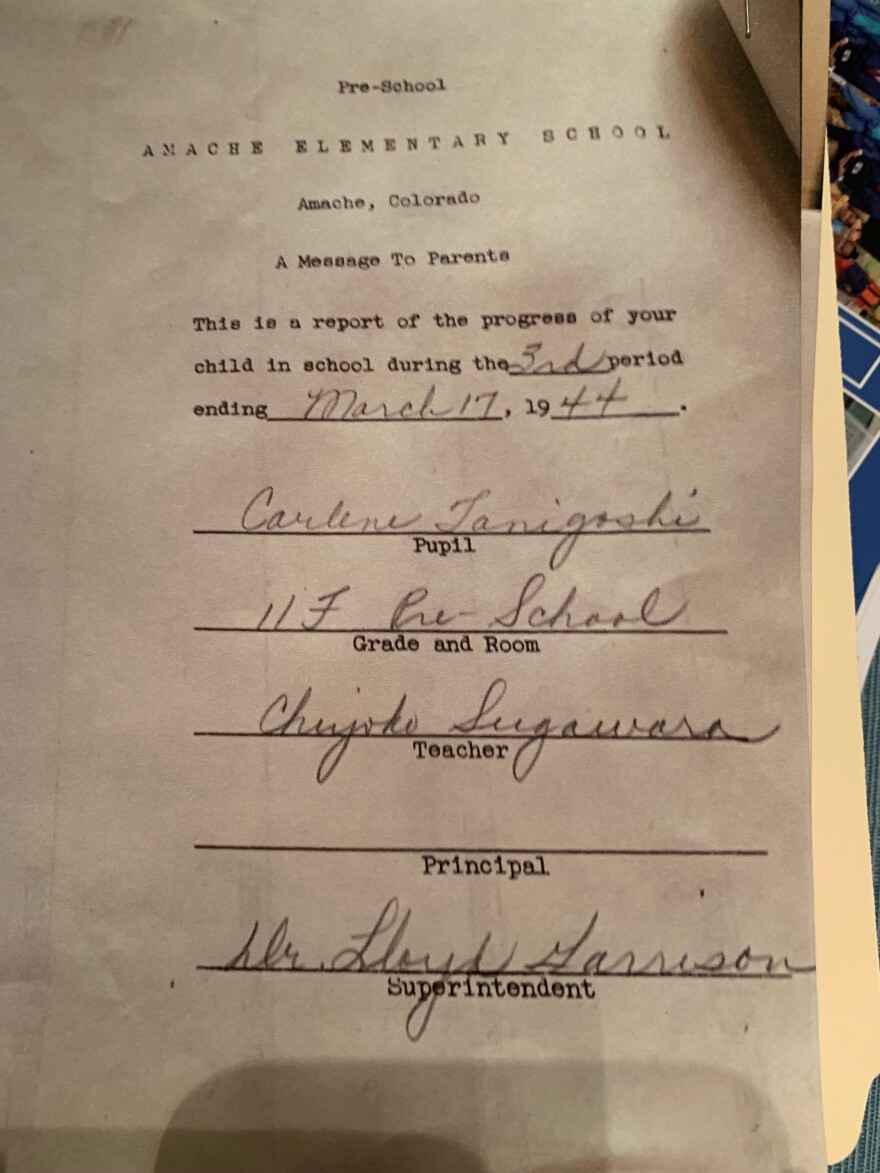

“I happened to be on the crew that was on the north side. And we were trying to figure out what was in the ground,” Tinker said. “I said, you know, this sounds pretty familiar, Block 11F.”

It wasn’t until Tinker visited the National Archives in Washington D.C. that this random excavation meant something more to her. She saw her report card on display – from the preschool in Block 11F.

“And guess what?” Tinker said. “That's how I found out that that was my preschool. … That was proof that I had actually been in that building in World War II from ‘42 to ‘45.”

She helped advocate for the building to be reconstructed. Now, it stands on its original footprint at the site, along with a water tower, guard tower and barrack.

Tinker believes everyone should have the same experience of discovering these pieces of history as she did.

“Every time I go to a field school [excavation], I learn something not only about myself, but also about the hardships and the lives of people who so valiantly survive this experience,” she said. “I think I was delighted that other people would have that same opportunity. And as they pass through, as they would visit the site, they will know more in detail what our story was.”

All these projects make one thing clear to Clark: Experiencing history in a physical way is key to understanding Amache.

“That kind of history is the sort of history that we engage with as like with our whole bodies and not just with our minds,” Clark said. “And I think that's critical for us to be able to, you know, walk in the footsteps of the ancestors.”

Amache will undergo some changes after being put under the umbrella of the National Park Service in March 2022, but seeing those changes could take years. In the meantime, the museum will stay open and the excavations will continue, so Hopper and Clark can keep telling people about a history that should never be repeated.

Part 3

Gary Ono is at home, leafing through some photos from the Amache internment camp in eastern Colorado. He was forced to live there as a child – along with thousands of other Japanese Americans.

“There's us standing out in the field,” he said. “Our barrack was kind of on the edge of that field, the baseball, football fields.”

At the time, his mom contracted tuberculosis, so she was sent to a hospital outside the camp to get treated. These photos were the main way his mother learned how he was doing.

“My Aunt Yuki took a lot of pictures of us kids and would send it to my mother,” he said. “So I see some photographs with, ‘To Kim. From Yuki.’”

And behind every photo, there’s a story.

“I remember when it was snowing, looking out of the window of our barrack and seeing the snow fall,” he said. “Earlier in the day, we had made a snowman.”

But as Ono grew up, he learned more about the World War II-era camp and saw it for what it was – a prison.

“You're older and you realize, what the heck is going on?” he said. “Why are we being treated this way? … I didn't get emotional at all until I realized and learned the ramifications of … being incarcerated in a concentration camp and having lost our freedom and having to live in a communal situation for nothing we did to deserve.”

Survivors like Ono knew they had to do something to preserve this history. Over the years, fewer and fewer survivors were around to tell their stories.

Ono himself is 82 – he wants to act before it’s too late. “I think it is important to know what we did go through, and appreciate maybe what our elders went through.”

Amache was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994, and later named a National Historic Landmark in 2006. But survivors wanted it included in the national park system, like the internment camps Manzanar and Tule Lake in California or Minidoka in Idaho. That required many more boxes to be checked.

Before anything could be done, Amache had to undergo a Special Resource Study. The site had to have national significance, be feasible and suitable for national park status, and have a need for park service management. The study was completed and sent to Congress in October.

New parks also must be approved by Congress. Tracy Coppola works for the National Parks Conservation Association, which fought for the legislation to make Amache a national park.

She said the success of Amache is built on the shoulders of the survivors.

“The larger community has really rallied for recognition for a type of justice that is long overdue and a place to honor the experience that was had at Amache,” Coppola said. “The absolute anchor in this, though, truly is the survivors.

“So like a real local homespun campaign where it wasn't just like people in D.C. saying, ‘We need this.’ It was like all the locals on the ground saying, ‘We need this, we need this bill.’”

After the survivors and descendants spent years pushing, the bill passed in Congress in February, a day before the 80th Day Of Remembrance for Amache on February 19. President Joe Biden signed the Amache National Historic Site Act into law a month later. Coppola said this will provide more resources and funding.

Read the Amache Letter to Appropriations Committee (PDF format)

“We're looking at a request for $505,000 for the Amache National Historic Site,” she said. “And hopefully that funding is going to support the first year of operations and five staff at the newly authorized site.”

That number was proposed by the National Park Service a few months ago, but President Biden and Congress still must weigh in.

Before the Park Service got involved, some stakeholders held quarterly meetings and drafted their own plans for what they wanted to see at Amache. Mitch Homma is one of the Amache descendants who contributed to those plans.

He said he will continue supporting Amache no matter how long the National Park Service takes. “We don't necessarily want to stop and just wait for the National Park Service. We're trying to do a lot of things in parallel and involve the park service on our current project, so when they do take over management, it dovetails nicely.”

John Hopper was also a contributor. He’s a local history teacher who has worked for years to preserve Amache, and he has many ideas gathered from survivors.

“We had for years, we had our own master plan,” Hopper said. “We sat down with Japanese Americans and worked this out with the Denver Optimist Club, Derek Okubo, and all them. … [We want to see] walking trails from the water tower all the way through that block with signages all the way down to the cemetery, and then the main gate with the visitor center and with that walking trail as well.”

Ono has more ideas for that list. He wants people to experience firsthand what he had to go through, starting with the lack of privacy in communal bathrooms.

“We even sat in toilets next to each other because they didn't have separate stalls. They just had rows of holes where people sat next to each other to go to the bathroom,” he said. “When you’re of mixed family, having to share the same toilet facilities, that has to be awfully embarrassing. Undignified.”

He also wants to see a mess hall added to the site. It might seem simple, but Ono said it changed the family dynamics in camp.

“The kids would always not want to necessarily eat and stick together with their own family. They would join their friends,” he said. “But, it kind of broke down a normal family structure.”

Some educators want to see classes at the site to teach about the history or create arts and crafts similar to those made at the site.

“For people to be able to go to Amache and learn how to make paper flowers just like they did back in the day … things like that I think would be really interesting,” said Bonnie Clark, a University of Denver archaeologist who does excavations at the site. “And that would be a way for this heritage to have that kind of active component on site.”

Despite these hopes and dreams, the site still has a long way to go.

“The site is not officially established as a unit of the park service until we've acquired the land,” said Kara Miyagishima, the interim superintendent of Amache with the National Park Service. “Once Congress approves the final budget for 2023, then we'll begin the lengthy process to fill critical positions.”

The town of Granada owns the Amache land, but plans to donate it to the National Park Service. That land transaction might not be complete until the spring of 2023 or even later. Until the park service gets the land, it can’t put federal funding into Amache.

“I think it will be a while before the public sees any changes to the site by the National Park Service,” Miyagishima said.

They also need to do a formal survey of the land, which Coppola said could take a few years.

“It's not a huge parcel, but it has been used for various uses and by a lot of different people and in a lot of historical uses over the years,” Coppola said. “There is a map that the congressional bill laid out. But it really needs to be formalized in terms of the boundary and what's on the land.”

Some progress has already been made. A team of key stakeholders and survivors has been put together to discuss the foundation document for the site. That serves as a big-picture outline of what’s important to preserve and interpret at the site. Members plan to meet in-person for the first time in January to discuss more of the details.

Coppola said this document is the anchor for most park sites. “Every park has specific things on the landscape that its staff really builds upon. For Amache, some of those themes are going to be just all the different stories to unpack and all the different ways the land was used and all the different experiences from the community.”

Miyagishima’s goal is to ensure the survivors are an active part of the restoration.

“We're making sure that we're telling the stories that are most important associated with the site and that we're preserving both elements of the physical site and also of the history that really resonate with the Japanese American community and especially the former incarcerated and their descendants,” she said.

Some stakeholders worry about a lack of funding. Hopper said last year, the cost of maintenance and remodeling alone was hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“I looked at their proposed budget for next year for that, it's not going to do much,” he said. “But maybe through the years they'll get more and more increased funding.”

Regardless of what happens with the site, survivors and the park service said that upholding this history is the chief goal. Ono agrees.

“It is not knowing the truth that causes a lot of misunderstanding,” he said. “So I think the more everyone can learn about each other, the better.”

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2023 KUNC. To see more, visit KUNC.