On a dam at the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge in northern Utah, the roughly 500-mile Bear River meets the Great Salt Lake. Mosquitoes and wasps swarmed the hunters and fishermen preparing for a day on the water on a recent morning, making these thousands of acres of marshlands seem less than inviting.

But for birds like the Wilson’s phalarope, this is a critical fuel stop on their journey from Western Canada to Argentina, said John Luft with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

“They usually have to double their weight when they're here so they can make it to South America on a nonstop flight,” he said.

Luft said that for 10 million-plus migratory birds, a shrinking Great Salt Lake puts their habitat under threat. The lake’s surface covered more than 3,000 square miles in the 1980s. Today, that number is less than 1,000, putting the ecosystem on the brink of collapse.

The consequences of a dried up Great Salt Lake affect more than just birds. It threatens Utah’s brine shrimp and mining industries. Ski resorts could also see less powder due to a decline in lake effect moisture. Additionally, toxic remnants of an industrial past could be kicked up into the air in toxic dust storms.

Joel Ferry, a fifth-generation Utah rancher and farmer who leads the state's Department of Natural Resources, said residents are becoming increasingly concerned about the iconic lake.

"People of Utah recognize that this is a real problem, and it's something that they personally are invested in now,” he said. “We have to recognize that it’s not an unlimited resource.”

Ferry said one key to reversing trends on the Great Salt Lake is preserving more water from the rivers that feed it, including the Bear River.

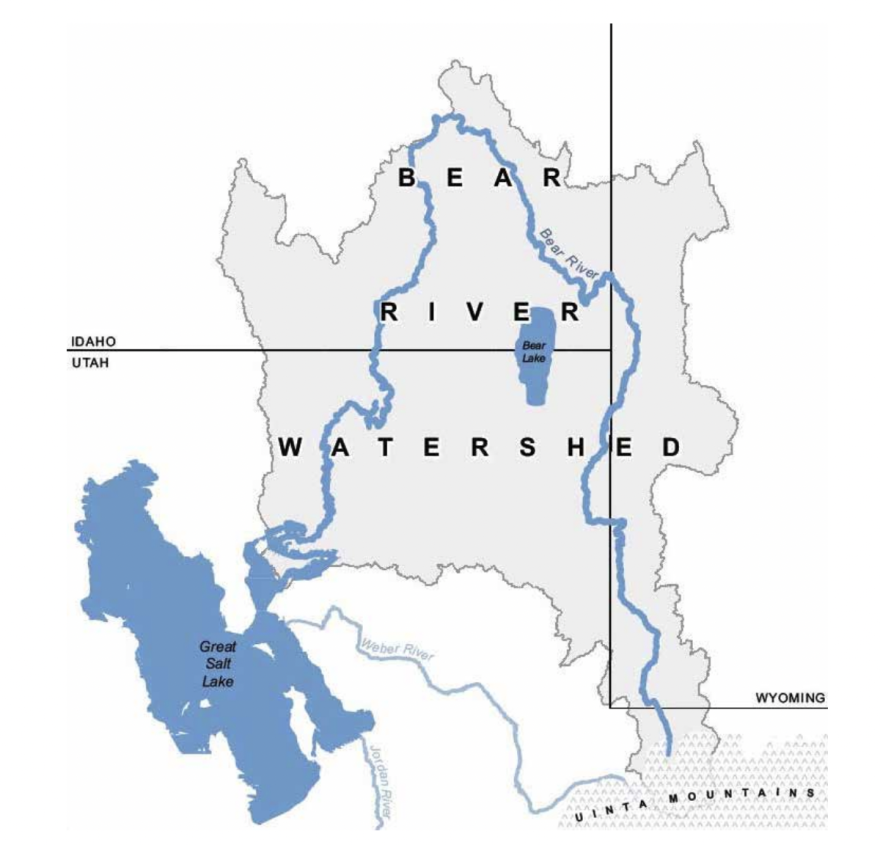

The Bear runs through three states in a horseshoe shape, and it is the largest river in North America that does not ultimately reach the ocean. It also supplies more than half the water flowing into the Great Salt Lake.

But the river’s watershed has had below-average precipitation four of the past five years, according to data from the National Resource Conservation Service. It also faces a lot of pressure from people who depend on it – and from climate change.

“The Bear River is the key to saving Great Salt Lake. And that's where our focus should be,” Ferry said.

Adrian Hunolt is a Wyoming rancher near the river’s headwaters, and he said he’s seen changes on the land he works.

“Seems like we're at the extremes up here now. So we'll have, like, an extremely low snow year, and then we'll have a tremendous snow year,” he said.

Hunolt lives at 7,800 feet mostly among windswept sagebrush fields. He said he has a 60-day growing season made possible only because he diverts water from the Bear River to his hay field. Hundreds of landowners in Wyoming, Idaho and Utah do the same thing per rights laid out in a tri-state compact.

“What I need to be able to do is bank grass during the summer so that I can use it in the fall and winter,” he said. “We've basically been irrigating these meadows here all summer.”

The water eventually gets filtered back into the river basin and Hunolt’s wetlands create habitat for birds, moose and beaver. But farming in the sensitive watershed is still controversial, especially in northern Utah.

A Utah State University study found that agriculture makes up almost two thirds of the water diverted for human use in the Great Salt Lake watershed. Hunolt points to development downstream as the problem.

“I don't feel like things have really changed that much up here at this spot in the valley in the last 150 years,” he said. “But the Great Salt Lake’s continued to dry up.”

Utah legislators passed a number of laws this year trying to get landowners to use less water. The governor also put a hold on new water rights, and the state may even pay farmers not to grow crops like alfalfa.

Joel Ferry said agriculture is willing to do its part to conserve.

“I see it in my neighbors. There's an inherent desire to make your farm better – to be more productive, to be sustainable,” he said.

What might not be sustainable, though, is population growth in Utah – 2.2 million new people are projected to arrive in the next four decades. A a years-in-the-making development project may divert more water from the Bear River to accommodate this growth.

With so many competing interests, compromises are going to be hard to find. The question is, can local legislators and residents figure out a fair plan to save the Great Salt Lake before it’s too late?

Editor's Note 11/21: An earlier version of this story did not include pictures or as much regional context. This piece has been updated to add in additional information.

This piece was also made possible through a reporting trip with the Intermountain West Joint Venture.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.