The best way to understand the controversy around "corner crossing" is to drive around on a county road through southern Wyoming. In the small town of Elk Mountain, passers-by can see pronghorn, elk, herds of cattle and very few vehicles.

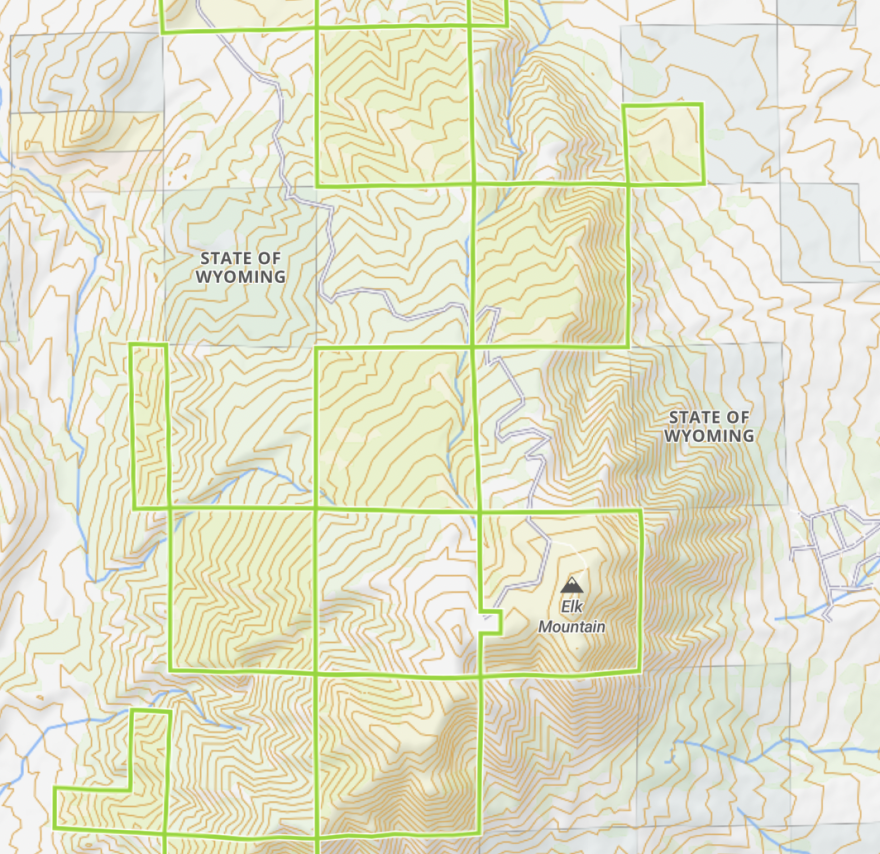

Here, like in other parts of the West with a lot of federal public land, fence lines can mark where private land ends and public land begins, forming a grid irrespective of physical geography. That’s a relic of the 1800s when railroad companies were granted plots in a checkerboard pattern as they traversed the region.

Today, it means parcels of public land and parcels of private land are intermingled with fences connecting at their corners.

Buzz Hettick is co-chair of the Wyoming chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. He said hunters, hikers and others once relied on topographic maps to negotiate public land boundaries. Today, he can move from one plot to the other with more confidence that he’s not setting foot on private property.

“It was just finding the corner pin and then just stepping from one piece of public ground to another piece of public ground using the GPS,” Hettick said.

This usually happens with no conflict. In fact, many private landowners allow hunters to access their properties or grant easements for safe passage.

But recently, corner crossing made headlines after four hunters from Missouri used a ladder to climb over a fence to access Bureau of Land Management land near Elk Mountain. They never set foot on the adjacent 22,000-acre private ranch and say they notified the local sheriff’s office prior to their days-long trip.

“The fact that they built the ladder – they contacted all these people – to me says they were doing everything they could to not cause conflict,” Hettick said.

But the landowner sued the hunters and charged them with trespassing. The main argument is that stepping over private property violates the landowner’s airspace. The lawsuit may force courts to bring clarity to what's long been a legal gray area.

Jim Magagna is executive vice president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. He often moves his sheep herds across the checkerboard.

“For us as ranchers, those boundaries between private land and public land and state trust lands and that, they exist on a piece of paper,” he said. “In most cases, they don't exist in terms of how you manage a ranching operation.”

However, he argues that allowing the public to move across those corners could severely damage his economic well being, safety and personal freedoms. His association has filed briefs in court supporting the trespassing charges.

“If the federal government is gonna control it, then we've devalued private property in the state in many instances because you no longer have control of your private property that we have all assumed we had,” he said.

At Elk Mountain, the landowner, Fred Eshelman, is a businessman from North Carolina with an estimated net worth of $380 million, per a 2014 Forbes article. He claims the damages just from that one corner crossing could be more than $7 million, as reported by WyoFile, a news organization that's covered the conflict extensively.

Recreators like Hettick argue a figure like that is a “scare tactic.” A Backcountry Hunters and Anglers GoFundMe campaign to help cover legal fees has raised more than $85,000 from nearly 2,000 donors.

“I mean, how do you own the air? You can't own air. I don’t see how,” he said. “His grievance is with the real estate company that falsely told him that he had exclusive use of that public ground.”

Lawyers representing the landowner didn’t respond to requests for comment.

This summer, the hunters were found not guilty for criminal trespassing by a jury in Carbon County, Wyo. But the outcome of a federal civil case against the hunters could have a major repercussions. One study found that more than 8 million acres across the West are corner-locked. Tens of thousands of corner points exist throughout the region.

“There are millions of acres of public land across the West that are not necessarily accessible to the public,” said Aaron Weiss with the nonpartisan think tank Center for Western Priorities. “Hopefully, this lawsuit will eventually straighten out.”

In a search for compromise and a clear resolution, Weiss advocates for creating corridors on each corner defining where the public can and can’t cross. Hettick argues that many corners should be restricted just to foot traffic to minimize impact on the landscape.

The Stock Growers Association recommends land exchanges to eliminate these choke points where private landowners don’t want to cooperate or where a corner crossing isn't feasible. Magagna said there are many tools that allow ranchers, for instance, to grant access on a volunteer basis.

“The picture that we all have in our mind now – the two posts with heavy chain and padlock, I mean that's not what a typical landowner’s doing everyday,” Magagna said.

However, no matter the outcome of the case, the lawsuit has already had an impact.

Liz Lynch was a vegetarian for half of her life before she discovered hunting and reevaluated her relationship with food. She mostly hunts on public lands, but disputes like the one near Elk Mountain still worry her.

“It's scary,” she said. “I don't want to have to be the next person paying $30,000 to cover attorney fees for two misdemeanors.”

Wyoming isn’t the only place where folks are fighting over public access. In Colorado, anglers are sparring with private clubs over fishing rights. In Utah, tensions are escalating between the U.S. Forest Service and a landowner over a road to a popular skiing and hiking spot.

Weiss said conflicts like these are likely to keep happening, especially as GPS technology keeps improving and more folks flock to public lands.

“As this changing West comes in – the billionaires buying up ranches, climate change drying up grasslands and ranch land – all of that together creates this very fraught scenario,” he said. “All of it is coming to a head in this Wyoming case, and in the Colorado stream access case. They're all different facets of the same coin I think.”

The corner crossing lawsuit is scheduled in U.S. District Court for Wyoming next summer.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.